© Momo Tus

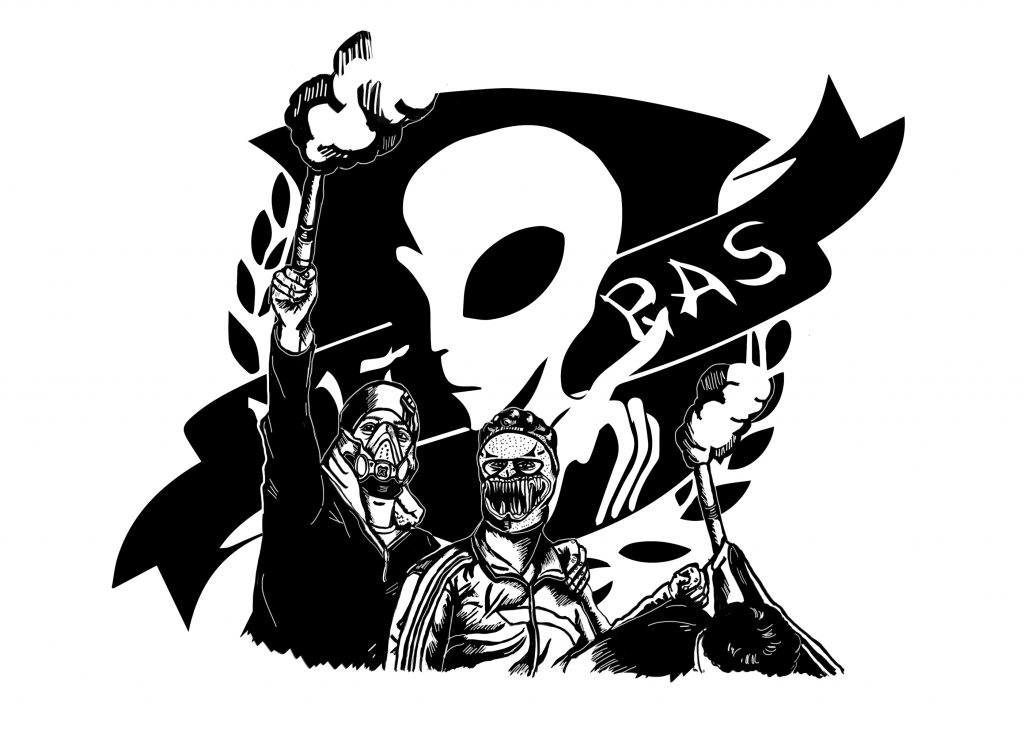

Both born in the White City, everything seems to tear Wydad and the Raja apart. From its origins to its « Ultras », does the Casablanca Derby only divide ? | By Momo Tus – Illus: Momo Tus – Trad: Julie B., Chris P.

Casablanca. Casa, for its close friends. An inscrutable feeling inhabits us. Hearing, sight, touch … The senses jostle, get lost, and meet again across the neighborhoods. Here, a visual cacophony. There, a sense of floating, silent and heavy. “Casa, the White”, with its 4 million inhabitants, sends us back this disconcerting image of an urban mosaic, made of mismatched bricks, from a modern to a dilapidated appearance.

Sit down. Wait. Look around. It only takes a few moments to soak up Casa and the tensions that run through it. In the neighborhood of the former Medina – Wydad’s stronghold, one the two main historic Casablanca football clubs – tranquility reigns between the merchant stalls and the immaculate white of the walls, yet reddened here and there by the supporters club ultras, the Winners.

Then, the night falls. The streets empty, the cold takes its marks among the Mercedes and the 4×4 running at full speed. The sky of Casablanca is dyed in its heavy orange glow, enhanced by the city’s subdued lights. A strange sensation it is, to witness the awakening of another Casa. It is a new night beginning, for those who like to trespass the limits of convention. And for those who go past the door of a storefront that looks like an empty, frying oil-scented restaurant : la Cigale. Then, behind a curtain in the back of the room, a bubble of smoky air is unveiled, far from the struggles and the constraints of the Moroccan conservative routine, punctuated with haram, halal and hchouma.

This is where we met him for the first time : Nabil. At the back of the room, in the darkness of his regular corner, we could only discern his little piercing eyes, almost entirely hidden by his cap and glasses. In his Ellesse padded jacket and his green hoodie — the colour of the Raja, Wydad’s enemy brother — Nabil introduces us, in between two phrases going like : « Naïma! Ten beers please! », to the two great Casaouis. In our hands, the ‘Spéciale’ beers come and go, and tongues start to loosen, under the (disapproving?) portrait of Mohammed VI’s little brother.

While some riffs were being played in the background by the Bar JukeBox, we didn’t come here by accident. We discovered the Raja Spirit with the song F’bladi delmouni, whose success crossed borders . Astonished, first. By this curve in full harmony, with hands perfectly synchronized while tending towards the sky. Touched, then. By this voice in unison, speaking to all the oppressed, the forgotten, from the whole world.Obviously, at the time, impressed, we frantically navigated from video to video of the Casablanca Derby and its tifos of unparalleled creativity.

Yet, it is as if we are missing a piece of the puzzle. There were too many “Whys” flashing through our heads. Why this song, while the Ultras have always positioned themselves as apolitical? Why so much fervor and creativity of these groups, however recent? Why, these two enemy brothers yet both born in the White City?

The locker-rooms : two clubs, two origins

‘‘One can tell you’re a Rajaoui from your character. It’s about people who come from oppression’’

Nabil takes a cigarette out of its pack. With his calm, grounded voice of heartened Rajaoui, he reminds us that the Raja is, more than anything, a matter of « history ».

Often forgotten, this story nonetheless sheds a vital light on the identity building of supporters today. We have to go back to 1949, back when the economic capital was mistreated by the French colons. Unlike the common idea, it was a group of the Moroccan National Movement, fighting for independence, which first initiated the creation of the Raja Club Athletic, as a vehicle for the emancipation of the people.

And it was not until 1962 that the club was taken over by Moroccan trade unionists from the Derb Sultan district, the cradle of the Casaoui resistance. Because of this political origin, power games are quickly being played within the Federation around the ascension of the club, the latter seeing itself regularly held back in the Championship or undermined as in the tripartite final of Raja / FAR / KAC from 1960.

Nabil stops. He’s looking for a word in French. Our Specials are empty. Our eyes, acclimatized to the half-light of the smoky cocoon of La Cigale, begin to tingle slightly. Naïma, decked out in her apron, returns with her arms laden with cold beers, and unpacks them one by one in record time. “You know .. a sport on the water… a bit like handball ..” “Oh yes, Water Polo?”.

Actually, they weren’t the first one. Twelve years earlier, the Wydad Athletic Club was founded in similar circumstances of resistance against the French protectorate. But this was done in exchange of very restraining concessions, like the partial control of the direction comity by the French, and the almost inexistent number of Moroccan players in the team. The sporting logic was nevertheless different since the beginnings of Wydad were initially built around a swimming team, which would be followed two years later by the football team of coach Haj Tounsi alias Père Jégo.

Nabil smiles, never missing the chance to titillate the Wydad. “You can tell by the fact that they are better today at Water Polo (Laughs)”. So that was it.

Unlike their rivals, during their early years Raja were by no means the most glittering club in the Championship. The Reds’ English physical and tactical game, led by Father Jégo, brought the Wydadis to the podium several times. But it is the Greens Eagles that raise the most excitement in the Casaoui popular districts. This excitement is reinforced by the team’s statute of « ugly duckling » in the Federation, which encourages the supporters to rally and protect their team.

Because the Raja isn’t only a football team : It is the team of the oppressed, the team of those who are put aside, those who are called « the poor », from the remote boroughs. As a result, Raja has long been considered “the club of the popular districts”, while Wydad, that of the middle classes – and current favorite of King Mohammed VI.

We begin to understand that, if it was in the 1960s – neck and neck in the Championship and with the creation of the Casablanca Derby – that their rivalry took on its full extent; the fracture is well beyond. Well beyond a spatial – between Casaoui neighborhoods – and social – class divide – but in people’s minds.

© Momo Tus

The field : two clubs, two styles

« It isn’t just about winning, unlike the Wydad. It is about winning the right way »

Today, the social fractures aren’t as evident, yet this is what gives them strength. The Ultras Winners thus include in their ranks young people from working-class districts of the Medina, as well as teenagers from well-off districts of Maarif. Moreover, it can happen that within the same family, the two camps clash. Nabil, whose own father is Wydadi, smiles, and taps his finger on the patch of his Rajawi sweatshirt. “My Uncle will never let me go through the door with this sweatshirt”.

The Rajaouis perpetuate this spirit of resilience, which is illustrated in an almost bestial way on the ground in the image of their history. By launching hostilities “The Wydad has acted and the Raja will react”, Father Jego turns his jacket over and goes to the enemy in 1952. The latter infuses the team with a game very inspired by South American football and Tiki-Taka from Barcelona. The Greens then turn their field into a live show, the Raja l’fraja, giving pride of place to technical, rather than athletic, qualities. A true sacred credo that may have created friction within the team itself, as evidenced by two players who one day came to blows because one had scored “without the beauty of the gesture”.

The Green Eagles then escalate quickly, fuelling their passionate rivalry with the Wydad, and win a double Cup-Championship in 1988 and 1989. It’s also what places Raja’s game far above Classico’s games and instills a sense of respect beyond Moroccan borders. The 80s and the 90s are therefore the consecration of a way of playing that combines show and victory, rallying more and more supporters.

The stands: two clubs, two curvas.

“When the Ultras started to sing, I got scared.”

Therefore, the match on the field between the two teams, is reenacted in the curvas between the Ultras. It all started in back 2003, with the supporters of the Celtic Glasgow, who, even though thousands of kilometers separated them, has something in common with the supporters of the Raja: the colour green.Due to the total absence of derivative products at the time, the most fervent Rajaouis began to wear Celtic FC t-shirts, scarves, caps, then drawing the outlines of a first collective group: the Celtic Glasgow Clique.

The southern curva, La Magana, was then waiting for its first Rajaouis Ultras to animate its seating rows. This is how the Ultras Green Boys 05 were born in 2005, committed to follow their team everywhere and at any occasion. The Winners, aka the Ultras of Wydad, followed the movement simultaneously the same year and settled in the North, at the Frimija.

But the war of the curvas is strong since personal and ideological disagreements quickly appear within the Green Boys– from chants to slogans- giving rise to the creation of the Ultras Eagles 05 in 2006, and then of the Green Gladiators (today disbanded). While the Green Boys remain the undeniable rivals of the Winners on the aesthetics level, with their high standing tifos, the Eagles, with their sharp words, pay very close attention to the message.

Thus, in the wake of their Tunisian and Algerian colleagues – notably their Ultras colleagues from Wifak Stiff – the three groups are introduced to Ultras culture. Organized by neighborhoods of Casa, tasks are assigned to each group core. Today, a single capo, Squadra, from the Green Boys, leads the two Rajaouis groups by mutual agreement after the incidents of 2016. No sound system, no tricks, just the arms, a voice that carries and a good dose of charisma to lead this impressive turn.

In a few years, both Reds and Greens have shown incredible creativity on the international Ultras scene, from the Room 101 Tifo or Shenron one. The Green Boys made three tifos for the first time in 2010 during a match, including two sketches that consisted of a double-sided tifo, (a number 3 world record).

Yet there is nothing innovative in their process of creation, if it is not abandoned deposits, dozens of plastic rolls, talented and thinking heads, and weeks of sleepless nights to make these tifos made entirely from the hand.

And this show war continues within the walls of the White City, where frescos testify to the enthusiasm brought by the two great teams. Recalling once again, like its origin, that this rivalry is not only pictorial but also spatial, where certain districts, like the old Medina, see their walls regularly covered with the bright red stencils of the Winners.

However, there are no more Ultras than “ordinary” supporters in the curvas. Unlike in Europe, the Ultras control the stands and the supporters rally the chants very easily – women included even if they still do not have a privilege to join the Ultras. Proof of this is that there are even groups of supporters like the Derb Sultan 49 (recently bowed out in February 2020) which have been involved since the creation of the club in the animation of the turn.

Once a hothead, always a hothead, even if the grandstands have settled down following the drama in 2016 of two deaths and a two-year official ban, the warm blood continues to flow in the veins of Ultras Rajaouis. If Hooligan and Ultras cannot be mixed up, post-match violence we have seen and reviewed. Nabil gives us a serious look. He points to the sturdiest of us, and says in one fatal sentence: “You can’t go there alone. It’s too dangerous“. But it is not the Ultras who create this violence: it is violence which already exists in the society.

Suddenly, we understand that – no – the bestiality of Ultras Rajaouis is not that of all Ultras. But to stigmatize and blame the Ultras for this violence would be far too easy, because the Ultras did not create violence: violence already exists in the streets and is only a reflection … of Moroccan society.

The stadium: two clubs, one people

“All the supporters sing for their team, whereas the Raja has always sang for the people.”

Though the Eagles originally composed the song F’labdi Delmouni in 2018, it is not the first, not the sharpest, nor the most accusing of the Ultras’ songs. Ya Lbabour Ya Mon Amour, Babour Liberté… were already chanted during the movement of the 20 th February in 2011.

Today, the stands have become privileged places of another form of expression – punctual – which brings together the two sides of the stands. Once unthinkable, concerted actions between supporters of different teams are now possible. At that point in the discussion with Nabil, we were convinced that it was political. With hindsight, it was surely our vision of the West that had something to do with it, because of the links that could exist, particularly in France, between Ultras and political engagement, far left, and far right.

In reality, it is not about playing politics at the stadium, quite the contrary: distrust of the political game is pervasive. The song, for example, is something purely human, universal.

Nabil puts his head on the palm of his hand while holding his cigarette with his fingertips. Looking far away, he ponders on how to explain this feeling to us. “When you’re alone you don’t dare, when you get in the stadium, it’s like a feeling of explosion within you.” In 90 minutes, the Rajoui can feel a whole range of emotions, from when he’s in the field to his daily life: the joy, the suffering, the hatred, the anguish, the admiration, the injustice.

The shout of a people who spontaneously feels the need to put in words, to give voice, to sing their daily angst in a country where the peer pressure is above “being yourself”. In a society where freedom of speech is condemned in favor of pretense, street protest is repressed in favor of the injunction to respect authority, and where not everything can be said, anytime. Because those curvas are theirs, it’s their Magana, their territory, their breath of air, their rules, their rights, so the Rajaouis collectively feel this confidence to express themselves freely and say things that ‘cannot be said’ outside.

© Momo Tus

Apolitical – but closely watched and feared. Just because they are among those “who dare to speak”, the Ultras groups are closely monitored by the authorities (body-searches, tifo control etc) in order to avoid any development in political protest after the Arab Spring. Especially since no collective has managed to bring together so many young people in Morocco to date.

Therefore, because they are organized in the public space, they are considered an issue. Because the state must be the only one which organizes access to the city. The Stadium becomes the medium for face-to-face meetings between state censorship and youth – outside authorized state channels such as unions or parties.

The core group very often wears a balaclava, for fear of being recognized and then imprisoned. But this repression does not stop their resistance, as evidenced by the famous tifo “[INSERT Clean Text HERE]” or “[INSERT Logo HERE]” in reaction to the controls of the tifos in 2019 following a – political – misinterpretation – of the tifo Room 101.

Yet it is this choice of repression, and not channeling, that could push the Ultras – born of this culture of rebellion – to fall into greater violence.

The Casablanca Derby, the power of football

2 AM in the morning. It is time to leave behind the empty beer cans and cigarette butts piled up on our table at La Cigale. Passing through the door, we take advantage of the night breeze of Casablanca.

The oppressed against the wealthy, an aesthetic play against a pragmatic play … Both being children of the White City, everything seems to draw away the Wydad and the Raja. Everything except the love for the round ball. It should not be overlooked that, at its origins, football has been taking this structuring role that is both about identity as well as geographic, in relation to the spaces in which it is developed.

If this role was somewhat lost through a certain starification of football, the derby would also lose its primary meaning: the confrontation of two rival teams from the same city. And yet it is through this form, just like the Casablanca Derby, football reveals all its power as a spatial division – separating different districts and spaces of a single city – to a social division – by giving an identity and values to an entire population according to the team supported.

Something clicked in our minds. We listened, understood, and answered our “Why”. Then, in our turn, we wanted to be Rajaouis. To think like a Rajaoui. To be proud like a Rajaoui. To challenge, like a Rajaoui. We understand that the anti-establishment practices of the Ultras are difficult to assimilate to political engagement. Rather, they are initially a reflection of the history of Raja, which over the years has succeeded in perpetuating its popular, resilient and rebellious collective identity against the state authorities. But also, the reflection of his city. Casablanca. Casablanca has always resisted, history proves it despite its dark moments. Then, finally the reflection of Moroccan society, lonely and ignored again and again by its leaders.

Cities Left Behind Playlist – Morocco

Listen to the full playlist here !