A fiction inspired by the book Rino Della Negra, Footballer and Partisan, by Dimitri Manessis et Jean Vigreux of the Libertalia Editions and the short story “Rubrique Sport” of Didier Daeninckx. The titles are taken from the two letters sent to his brother and his parents, before his death.

Article & Illustrations by Momo Tus

“I embrace all of Argenteuil, from the beginning to the end”.

On this chilly autumn night of 1943, the steam on the windows and the acrid smoke from the stoves only let glimpses of shadows that seem to come alive for dinner time. Rino jumps from plank to plank, placed there along the path to avoid wading through the quagmire smelling of burnt garbage. He smiles: Mazzagrande – the “Great Manure Pit” at the northern tip of Argenteuil well deserves its name. He stops abruptly. At the end of the street, the top of the hill sparkles, as every evening, some workers still find themselves in the gypsum quarries to be digged, in the dark.

Rino thinks of his Italian brothers from the Emilia-Romagna region, driven out by Mussolini’s black shirts – like his parents – and massively mobilized to rebuild France alongside Poles, Belgians, Czechs. He has worked with them since he was 14 at the Chausson factories in Asnières-sur-Seine. As a radiator fitter, he worked for 4 years, with his mother, Anna, a tin welder.

The repetitive enslavement to the chain, the roar of the torches and the hammering of the clashing sheets, the harsh smell of burning. We get used to it. Until you forget your own existence.

“And get drunk thinking of me”.

In the distance, a few laughs brighten up the unhealthy darkness of “Little Italy”. They escape from Mario’s, the café-grocery store and its famous pétanque strip: this is where the last ones left share a few carefree moments despite the weight of the German occupation. Rino pushes the rickety wooden door with his hand. Among the bald heads sharpened with berets, he recognizes the singing verb of Gabrielle Simonazzi and Inès Sacchetti in full preparation for the next lottery.

Without saying anything, Inès discreetly slips him a ball of paper. Then he heads for the back door. It is in the back room that one of the clandestine cells of the Communist Party meets today. Rino gives a discreet nod to his friend Tonino Simonazzi, decked out in a white shirt, denoting with his jet black hair falling over his forehead. He raises his right arm with difficulty to greet Rino, a bruised memory of the International Brigades at barely 20 years old.

“Embrace all athletes from the youngest to the oldest. Say hello and goodbye to all the Red Star”.

The bells ring below a few steps from the Seine. Rino does not stay: it is 7 p.m. and his team is waiting for him. Rino goes out, hurries to reach the boulevard Jean Allemane where the Gendarmerie is, created before the school: “Because it is a neighborhood of immigrant bandits”.

Arriving in front of the gates of the Stade Henri Barbusse, he sees his captain, Léon Foenkinos, from afar, who chants with his singing accent of Algerian pied-noir “What are you doing, we are waiting for you!”.

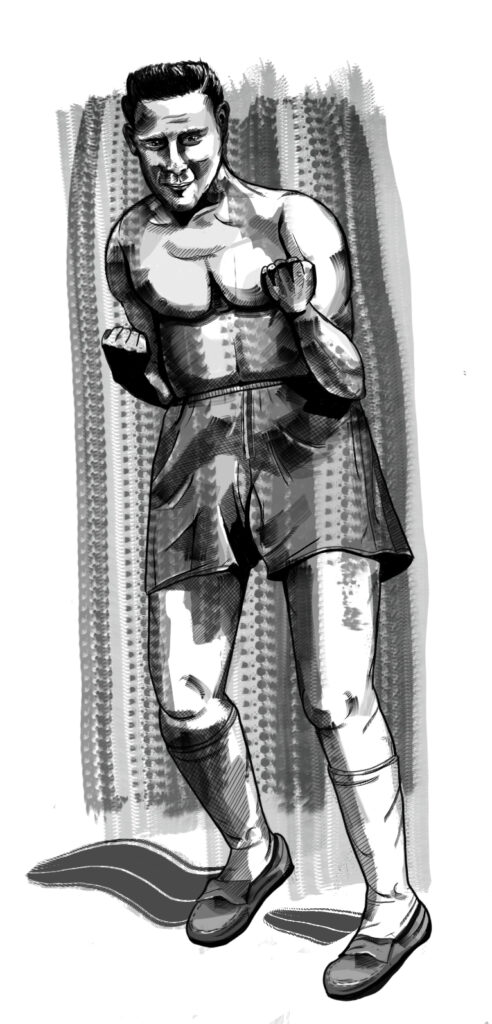

Spotted a few months ago by the Red Star club, champion of France in 1942, it must be said that Rino is an arrow: dismissed from the age of 14 at the Football Club of Argenteuil (FCA), he goes on to win prizes and cups in the area’s clubs, from the Usines Chaussons, the Jeunesse Sportive d’Argenteuil (JSA) affiliated with the Sports and Gymnastics Federation of Labor (FSGT) to that of the Union Sportive Athlétique de Thiais (USAT).

The front lines are moving the lines of Labor sport. The German-Soviet pact ratifies the exclusion, within the FSGT, of all the clubs which support the latter, before the FSGT itself ends up in a complacent attitude towards the Vichy regime, Olympic-Nazi salute included.

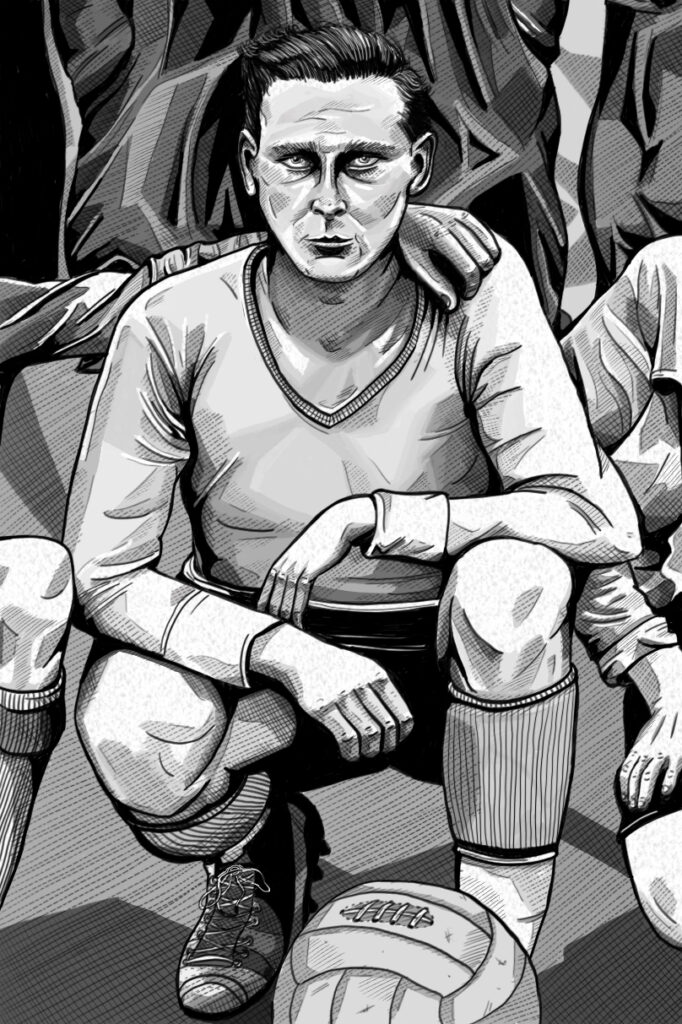

Rino is part of this tradition of workers’ football and not the least. A sprinter and regular 100-meter champion, Rino, a right winger, takes a point on the field, performs body feints and hooks, before delivering a powerful shot that surprises the goal. “It’s crazy, when he has the ball, the guys never catch him” then slips Dédé, his teammate on the bench, to Léon. They were convinced he was going to be a star. A few brief words in the locker room and Rino, hair slicked back and fluffy on top of his head, beige trousers with clips matching his raincoat, resumes the long journey towards the heights of Argenteuil.

“I regret very much that I never told you what I was doing, but I had to”.

In front of this small concrete house, proudly built, that evening, he does not move. In the quiet of the night, watching his mother through the window who was busy cooking. His eyebrows droop, the corners of his lips curling slightly into a worried smile. What will happen tomorrow? He pushes open the door, the warmth of the pan and the smell of soup wraps him in the sweet memory of his childhood. His mother from behind, a black kerchief catching up with her long black hair, jumps, turns around and looks at him, surprised. “What are you doing in Argenteuil? You’re supposed to work tomorrow!” Rino kisses her on both cheeks, “I just wanted to come see you before I go home”. In fact, he hasn’t come to the factory gates since February. Refractory to the Compulsory Labor Service, Rino is one of those who fell into hiding on the other side.

But that, no one knows, apart from his sweet friends, Tonino and Inès. He has become a completely different man, next door: Robin Chatel, single, domiciled at 4 Passage du Génie, in the 12th arrondissement, in Paris.

While his mother thinks he left at dawn every morning to meet the timekeeper, that’s how, almost a year earlier in 1942, his way, at the red crossroads of his friends from the suburbs and his football teammates, led him to rub shoulders with figures of Francs-tireurs et Partisans – Main-d’oeuvre Immigrate (FTP-MOI) such as Alfredo Terragni. Joining the greats of the combat resistance, he became a supporter of the 3rd detachment: known as “Gilbert Royer”, registration number 10,293.

When he is not on the field, Rino plays real ammunition.

Watcher or commando leader, he will be in 6 months one of the youngest triggers of 15 attacks against Germans, with the Manouchian group, Valmy and the Argenteuil FTP, including the attack against General Von Alexander Apt or the destruction of the headquarters of the Italian fascist party.

“The greatest proof of love is to give your life for those you love”.

Clandestine, Rino nevertheless continues his family visits and his sports record, managing to pass under the radar, like this evening. The next day, November 12, 1943, at 5 a.m., after patiently unfolding the little ball of paper, reading the instructions and tossing and turning all night in a bed offered by the Simonazzi, Rino rolls up the collar of his beige raincoat, sticks his hands in the back pockets of his pants and runs towards the river to catch the bus. The planked roads of Mazzagrande gradually giving way to the paved roads of the city center, he goes down to the gates of Paris to catch the underground iron dragon towards Vincennes. 7 am, he arrives at a bicycle garage where five bicycles are waiting. He recognized the large silhouette of Secondo (Alfredo Terragni), then of Paul (Spartaco Fontanot), Marcel (Cesare Luccarini), Marc (Georges Cloarec) and René (Robert Witchitz).

He did not know, until this morning, the identity of those who were to cover him and was immediately reassured of Manouchian’s choice.

He gets on his bicycle and sets off again, the adrenaline rising as fast as Rino picks up speed as he goes up the boulevards. In his hideout in the 12th arrondissement, lost in his thoughts in this cramped and bare space, time passes quickly and he must already leave. He arrives at the Reuilly-Diderot metro, runs down the steps, hands the ticket to the ticket inspector and rushes into the first train. It’s 12 o’clock. It is at the exit of the Métro Cadet that he sees Inès. It is his “courier”. Hidden from view under a porch, Inès stealthily opens her double-bottomed briefcase: Rino unrolls the stained rag and grabs the 6.35 caliber Bergmann to store it in the back of his pants. One look and he leaves her. Rue Lafayette, he recognizes Secondo stashed in a hall, right next to a bank where the two German cash couriers in civilian clothes are. He continued on his way, turned right, then right again, to return to the beginning of the street. The five other men were already there, camouflaged in the crowd. Eyes meet, without a word.

He and Robert are cutting edge. The two men land to the right of the glass door of the café at 56 rue Lafayette and pretend to carefully scrutinize the derailleur of Robert’s bicycle.

A few glances through the window confirm the presence of the two conveyors who are leaving the cafe. Rino gets up, walks past the storefront, and positions himself to the left of the revolving door. Leaning against the wall, he discreetly push aside the tail of his raincoat and ran his hand over the small of his back to feel the cold butt of the caliber. A first click of the heel on the threshold of the door and the six men in hiding suddenly stiff. The two conveyors move forward, and Rino, right in the middle of the crossroads, extends his right arm in perfect alignment with the rest of his body, and, inches from the back of his target’s neck, he fires. The conveyor with the leather briefcase collapses.

But, Rino also collapses. Hit in the kidneys, he tries to flee as his last vision was his teammates under a rain of projectiles. He will be shot on February 21, 1944 at Mont-Valérien, alongside 22 of his comrades who’ve been watched and tracked for several months.